[Page 1 - Title Page]

The Mycenaean Atlas Project is a relational database dedicated to storing accurate locations of Late Helladic find spots in continental Greece and the Aegean. It has taken six years to reach this point; the effort is entirely self-funded.

[Splash Page Slide]

Shortly after beginning the DB work I began to develop the software to put the DB online. This is the site Helladic.info; there is open access to this site - anyone may use it. It currently hosts nearly 4500 site pages as well as 6500+ sites - not Bronze Age - that I call Features. These include things such as towns, bridges, churches, etc.

The use of the site is straight-forward. The easiest way is to enter a site name such as 'Mycenae' or 'Tiryns' in the search box and then click on the returned link. This will bring you to the correct site page. The site page itself has a search box so that you can, if you wish, continue with another search or you may return to the control page.

[Goals]

The tool allows quick reference to specific individual sites. It should allow researchers at whatever professional level to quickly investigate the several sites which characterize Bronze Age Greece. These goals include allowing users to have accurate coordinates for sites, to generate reports, and to use the DB in follow-on uses.

It features an intuitive user-interface that allows for easy exploration of the BA landscape. There is a dedicated page for each of the 4400+ sites. The DB is accessible in several ways which include a nearly-completed API. Those researchers who would like to obtain the full DB should contact me through e-mail.

[Slide of control page]

This is the central (or 'control') page for the site. It provides a variety of search methods for zeroing in on the site(s) you would like to investigate. Besides a General Search that allows you to search for any string there are other search types

- Search by region (2 ways)

- Search by combination of region, ceramic horizon, and type

- Search by well-known or important sites

- Search by gazetteer contribution ('literature')

- Search by habitation size (sq. m.)

- Search by elevation range (m.)

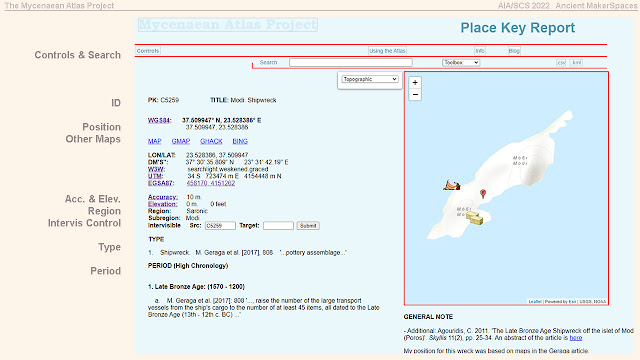

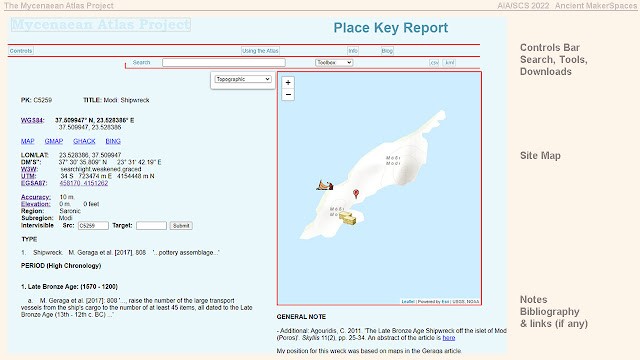

[Slide of a single site page]

\

Each site has its own dedicated page with

- Locational information

- Accuracy indicator

- Elevation

- Type of site and finds

- Ceramic horizons associated to the site

On the right-hand side of the individual site page we have the

- Location Notes

- Site Bibliography

[Slide of four individual site tools]

Tools for individual sites

- Intervisibility: This shows all the sites in the DB which are intervisible with your chosen site. It looks out 6.5 km.

- Aspect and Slope: This analyzes the slopes at the site and tries to show which direction the site faces

- Nearest neighbors: This draws a map which shows your site's nearest neighbors along with the direction to those sites.

- Three dimensional modelling of the site environment: There are 3D terrain models for most of the sites; these were prepared for me by Xavier Fischer of elevationapi.com.

[Slide of four types of analysis for groups of sites]

Groups of Sites

In addition to single sites you can also analyze sites as groups, e.g. all peak sanctuaries or all sites in Messenia. You define these groups from the Control page. If you want to group sites from certain regions then you can choose those regions from the handy thumbnail maps on the Control page. Once your group is created you can generate group reports:

- Group aspect: This report looks at the slopes and aspects of all sites in the selected group

- Gazetteer: This deceptively simple list of all sites in the group turns out to be among the most useful reports. The gazetteer has info on each site along with a link to each site in the group.

- Elevation: The elevation report lists the elevation for each site along with a histogram and elevation graph for the group. It also provides other statistics.

- Specialized Bibliography: After you've selected a group the Bibliography Report will generate a list of sources that were used to create that group.

- Chronology: This generates a chart of all the ceramic horizons that are characteristic of the group you selected.

[Slide of data sources: BIBLIO]

I began this Atlas with a copy of Simpson's Mycenaean Greece from 1981. At the start I supposed that I had no need for a bibliography table in the DB. Simpson would be enough. By the time I reached my third site I had seen the error of my ways; at the present time the bibliography contains 1700+ titles and may be seen by anyone using the website. On the Controls page you may examine the Atlas' coverage of any of the 40 most significant Gazetteers used in creating the DB. The sites were located in various ways, through gazetteers with good locational information, examination of maps such as Topoguide, Topostext, ... even user contributions such as Wikimapia. On my blog there are many examples of the techniques I used to find specific sites. The internet has given wide access to the scholarly literature and many a dissertation was examined for information. Each site was, if possible, confirmed in several ways before being put in the Atlas.

[SEARCH and HELP SLIDE]

There is also a powerful search facility and an extended help page.

You can search by any string and especially by the place keys. The results come back as links to the page on which that string appears. This includes find spots and periods, author and book names, contents of notes, etc.

Summary and Future

API or Application Programming Interface.

1. There are any number of online databases that can be integrated to this software. When you design software you should take note of other databases that can enhance your own product. The elevation.api Interface is an example of this but there are other DBs such as hydrography or geology that may add to and enhance your product.

2. One use of this DB may be to use the tables independently in other completely different DBs. You may for example be developing a DB on Mycenaean weapons. In order to express the location of these finds you will have access to a kind of Mycenaean Site API that would 'serve' locations to online clients. The API should be able to serve elevations, lat/lon pairs in several types, alternate names, lists of ceramic horizons, biblio names, etc.

3. It's not clear to me that for a product of this type a simple lat/lon to name pairing will be adequate. Sites need a story to go along with them. An approach like Topostext.

4. In the area of ancient history, ethnography, linguistic studies, etc. (everything having to do with antiquity) it is necessary, like the hard sciences, to 'save the data'. We cannot stake the future of knowledge representation and programming in this area to 'semantic networks' or 'webs' with their suffocating 'ontologies' or 'controlled vocabularies'. Such things are advocated by some, not for any reward for the Humanities, but solely for the convenience of the computer.

[Thanks to contributors]