|

| Desert kite in Lebanon at 32.177468° N, 37.224406° E |

|

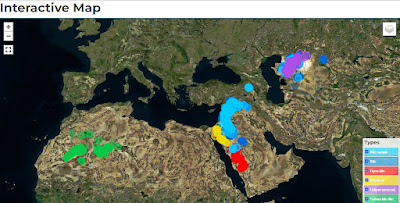

| A coverage map by the Globalkites group. The areas where kites are recorded include West Africa, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Syria, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. |

This is a good example of a game drive system on [9] The trap is nothing but a series of upright poles into which the reindeer are driven. Once they're funneled into the corral they can be sorted for domestication or killing.

What is genuinely counter-intuitive about this method of hunting is that these stone lines (even when they are continuous) are rarely very high; in all cases the game can easily step over them but do not do so.[7]

Scotland provides examples of a rather different type of game drive systems. The Reverend Donald Maclean (1796) gives an account of such a system on the island of Rum in the inner Hebrides: "Before the use of fire arms, their method of killing deer was as follows: On each side of a glen, formed by two mountains, stone dykes were begun pretty high in the mountains, and carried to the lower part of the valley, always drawing nearer, till within 3 or 4 feet of each other. From this narrow pass, a circular space was enclosed by a stone wall, of a height sufficient to confine the deer ; to this place they were pursued and destroyed. The vestige of one of these enclosures is still to be seen in Rum." [10]

It appears that game drive systems in Scotland did not always consist of walls. Dean Monro tells us that sometimes it was only necessary to drive game between two bodies of water. On the island of Jura in the Inner Hebrides the Dean tells us that

"… there are two salt water lochs meeting each other through the middle of the island to within half a mile. And all the deer of the west part of the forest will be brought by an encircling movement to that narrow entry, and the next day brought west again by the same movement, through the same narrow place, and an infinite number of deer will be slain there." [B]

Narrow valleys or glens would suffice for the channeling of deer.

Glen of the Bar (55.007110° N, 4.380103° W) is a narrow valley reputed as a place for trapping deer.

|

| Glen of the Bar. Letter 'A' marks the high point of the valley and the spectator lookout. |

|

| Glen of the Bar from the lookout. View is to S. |

Another drive system installed on 'low ground' is at Loch Ruthven. "The Strathnairn Elrick is near the east end of Loch Ruthven, on the low ground, where there is a pass or small glen, overlooked by a 'cragan'."[11]

Watson may be referring to the low ground here: 57.323329° N, 4.247311° W. The map shows it as 'Elrig'.

The word 'Elrick' or 'Elrig' features often as a place name in Scotland. The word means 'Deer Trap'. [12]

Summary

Hunting in antiquity was often carried out by large groups. Sometimes, as with boar, the quarry was too dangerous to approach by one person.

But even Hunting of ungulates in antiquity was often carried out by large groups of people taking multiple deer at the same time.

This activity was seasonal. Does going north with baby deer to feeding grounds after birthing.

What was used were narrow valleys, netted or hedged structures, as well as lines of rocks, cairns or poles which would serve to draw the deer (Red Deer, Fallow Deer, Roe Deer) or other ungulates (antelope, gazelle, reindeer, caribou) into a central killing or capture zone. These drive structures were usually accompanied by specific hides or ambush sites..

Kill sites Hunting was often not just an activity. It was a landscape. That is because many other activities are necessitated by large kills. Such connected activities would include butchering, skinning and skin preparation, cooking, drying or preserving, and caching.

Footnotes

[4] In the Klissoura cave in northern Argolid deer were represented in every level from the mid-Paleolithic to the Mesolithic. Stiner et al. [2010] 314. Klisoura Cave 1 is fronted by a narrow valley and suggests that it was used as an early game-drive system. As food: Starkovich [2012] 13, " ..., previous studies indicate that the archaeofaunas at Klissoura Cave 1 are dominated by a single species, fallow deer (Dama dama) ... . The taxon comprises 60-91% of species-specific identifications in the Middle Paleolithic, and 12-78% in the Upper Paleolithic and later layers, though there is variation between assemblages, particularly in later periods ... " The existence of some 50 clay-covered hearths suggests that meat preparation and cooking may have been done on a large scale. Karkanas et al. [2004] 522 say that the hearths at Klissoura Cave 1 were associated with bones of fallow deer (Dama dama), hare (Lepus europaeus), rock partridge (Alectoris graeca) and Great Bustard (Otis tarda).

Elsewhere the Red deer (C. elephas) is represented, e.g. in the Franchthi Cave. Douka et al. [2011] 1143.

[4a] Benedict [2005] 432, "At times during the past, the Copper Inuit or their Thule ancestors established substantial settlements near game-drive sites along caribou migration routes. Facilities for drying and storing large quantities of meat were associated."

[4b] It may be appropriate to mention here the hypothesis that the cursuses of Britain, Scotland, and Ireland are an early form of game drive system. Fletcher [2011] position 1074 says "I hesitate to suggest that they may ever have served as a means for killing deer ... but similar constructions were later to be used to direct deer." What seems most compelling to me is that at one of them, Woldgate Cursus terminal at Rudgate in Yorkshire, arrowheads were found. The specific spot is here: 54.076233° N, 0.320543° W. Woldgate Cursus is reviewed in McOmish and Tuck [2002] 28 who provide a photograph of the arrowheads. The Woldgate Cursus is also described at this website and this website. There are a number of fantastical theories about the construction and use of cursuses. These theories are reviewed in Maguire [2015].

[5] Globalkites is here; their interactive map is here.

[6] Nubia: Storemyr [2021]. Tibet: Fox and Dorji [2009]; North America: Colorado: Benedict [1975], Benedict [2005]; Brink [2005]; Canada: O'Shea et al [2013]; Norway: Olsen [2013]; Scotland and England: Watson [1913]; Fletcher [2011].

[7] Benedict [2005] 432 quoting Stefánsson [1921]: "'It seems absurd,' wrote Stefánsson (1921, p. 402), 'that two stones, one on top of the other, reaching an elevation of only a foot, should be feared as much by the caribou as actual persons but that appears to be the fact.'

[A] An 'impound' system drives the animals into a corral where the priority is to capture and domesticate them.

[8] Olsen [2013] fig. 14. No page numbers in the online edition. The position is at roughly this location: 61.853444° N, 8.962183° E

[10] Watson [1913] 162. The island of Rum is here: 56.999030 N, 6.329717° W.

[B} As reported in Watson [1913] 161. Translation is by Fletcher [2011]. The Kindle position is 1427.

[11] Watson [1913] 164.

[12] For etymology and definition see Watson [1913] 163: "The Elrick was an enclosure, usually in relatively low ground, into which deer were driven by the 'tinchell'." Tinchell, also tainchell, are beaters.

Also in Fletcher [2011] : "I wish to mention briefly the Scottish equivalent known in Gaelic as an elrick, or sometimes also referred to as elerc, an Old Irish word in origin which refers to the spot at which driven deer might be ambushed in a narrow defile." No page numbers in the online edition where the position is given as 1384.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

[2] Feldman and Sauvage [2010] 133.

[3] Evenson [2002] "A lone hunter from the light background turns and faces to the right, poising to spear a stag who is running left towards him across the wavy zone-change line (cat. no. 16H43). These central opponents are, in de Jong’s reconstruction, the only figures who strike active poses, the other hunters and dogs moving in processional form across the panels."

[4] Halstead [2002] "The same general observations can be made from this year’s work as were made last year: the material is strikingly more mixed anatomically, taxonomically and taphonomically than the big groups of burnt bone studied in 2000; by far the commonest taxa are pig and sheep; and red deer continue to be the commonest wild animal"

Bibliography

Achard-Corompt et al. [2013] : ACHARD-COROMPT, Nathalie (ed.) ; RIQUIER, Vincent (ed.). Chasse, culte ou artisanat ? Les fosses « à profil en Y-V-W »: Structures énigmatiques et récurrentes du Néolithique aux âges des Métaux en France et alentour. Dijon: ARTEHIS Éditions, 2013. Online here. ISBN: 9782915544718.

Anderson [1985] : Anderson, J.K., Hunting in the Ancient World. University of California Press, Berkeley, California. 1985.

Barringer [2002] : Barringer, Judith. The Hunt in Ancient Greece. Johns Hopkins University Press. 2002.

Benedict [1975] : The Murray Site: A Late Prehistoric Game Drive System in the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Plains Anthropologist (20(69)), 161-174. 1975. Online here.

Benedict [2005] : Benedict, James B., 'Tundra Game Drives: an Arctic-Alpine Comparison', Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research (37:4) 425-434. 2005. Online here.

Betts and van Pelt [2021] : Betts, Alison, W. Paul van Pelt. The Gazelle’s Dream: Game Drives of the Old and New Worlds. Sydney University Press. 2021.

Brink [2005] : Brink, J. W., "Inukshuk: caribou drive lanes on southern Victoria Island, Nunavut, Canada". Arctic Anthropology , 42(1): 1-28. 2005. Online here.

Broneer [1966] : Broneer, Oscar. "The Cyclopean Wall on the Isthmus of Corinth and Its Bearing on Late Bronze Age Chronology", Hesperia (35:4), 346-362. The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 1966. Online here.

Broneer [1968] : Broneer, Oscar. 'The Cyclopean Wall on the Isthmus of Corinth, Addendum', Hesperia (37:1), 25-35, The American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 1968. Online here.

Buchholtz [1987]: Buchholtz, Curt. Rocky Mountain National Park: a History Published by University Press of Colorado, 1987. ISBN: 9780870811463

Crassard et al. [2023] : Rémy Crassard,Wael Abu-Azizeh, Olivier Barge, Jacques Élie Brochier, Frank Preusser, Hamida Seba, Abd Errahmane Kiouche, Emmanuelle Régagnon, Juan Antonio Sánchez Priego,Thamer Almalki, Mohammad Tarawneh, 'The oldest plans to scale of humanmade mega-structures'. PLOS ONE, May 17, 2023. Online <a href="https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0277927">here</a>

Douka et al. [2011] : Douka et al. [2011] : K. Douka with C. Perles, H. Valladas, M. Vanhaeren, R.E.M. Hedges, 'Franchthi Cave revisited: the age of the Aurignacian in south-eastern Europe', Antiquity 85 : 1131–1150. 2011. Online here.

Enloe [2003] : Enloe, James G., 'Acquisition and processing of reindeer in the Paris Basin', Zooarchaeological Insights into Magdalenian Lifeways. pp. 23-31. 2003. Online here.

Evenson [2002] : Evenson, Freya. '11. Hunting Scenes in the Frescoes', in Davis, Jack et al., <i>THE PYLOS REGIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT: 12th Season Preliminary Report to the 7th Ephoreia of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, Olympia on the Results of Museum Study August-October 2002</i>. Online here.

Feldman and Sauvage [2010] : Feldman, Marian H. and Caroline Sauvage. 'Objects of Prestige? Chariots in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean and Near East', <i>Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant</i> (20), 67-181 Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. 2010. Online here.

Fletcher [2011] : Fletcher, John (2011). Gardens of Earthly Delight. The History of Deer Parks. Oxbow Books. 2011. Kindle Edition. ASIN : B00BWAZBUG

Fox and Dorji [2009] : Fox, Joseph L. and Tsechoe Dorji, 'Traditional Hunting of Tibetan Antelope, Its Relation to Antelope Migration, and Its Rapid Transformation in the Western Chang Tang Nature Reserve', Arctic Antarctic and Alpine Research , 1-15. May, 2009. Online here.

Gregory [1993] : Gregory, Timothy E. Isthmia V; The Hexamilion and the Fortress . American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Princeton, N.J. 1993.

Halstead [2002] : Halstead, Paul. '5. Museum Study of Animal Bones', in Davis, Jack et al., <i>THE PYLOS REGIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT: 12th Season Preliminary Report to the 7th Ephoreia of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, Olympia on the Results of Museum Study August-October 2002</i>. Online here.

Karkanas et al. [2004] : P. Karkanas, M. Koumouzelis, J.K. Kozlowski, V. Sitlivy, K. Sobczyk, F. Berna and S. Weiner. 'The earliest evidence for clay hearths: Aurignacian features in Klisoura Cave 1, southern Greece', Antiquity (78), pp. 513–525. 2004. Online here.

Maguire [2015] : Maguire, Kristyn M., 'Topographical Relationships between Cursus Monuments in the Upper Thames Valley', Thesis submitted for the Master of Science in Applied Landscape Archaeology in the Department for Continuing Education, University of Oxford, United Kingdom, 2015. Online here.Morgan [1999] : Morgan, Catherine. Isthmia VIII; The Late Bronze Age Settlement and Early Iron Age Sanctuary. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Princeton, New Jersey. USA. 1999. ISBN: 0-87661-938-3.

Olsen [2013] : Olsen, John. 'Hunting using permanent trapping systems in the northern section of the mountains of Southern Norway: focus on wild reindeer', <i>Chasse, culte ou artisanat ? Les fosses « à profil en Y-V-W »: Structures énigmatiques et récurrentes du Néolithique aux âges des Métaux en France et alentour. Dijon: ARTEHIS Éditions, 2013. Online here. ISBN: 9782915544718.

O'Shea et al [2013] : O'Shea, John and Ashley K. Lemke and Robert G. Reynolds, 'Nobody Knows the way of the Caribou”: Rangifer hunting at 45° North Latitude', Quaternary International (297), pp. 36-44. 2013. Online here.

Prummel et al. [2011] : Prummel, Wietske and Marcel J.L.Th. Niekus 'Late Mesolithic hunting of a small female aurochs in the valley of the River Tjonger (the Netherlands) in the light of Mesolithic aurochs hunting in NW Europe', Journal of Archaeological Science (38:7) 1456-1467. 2011. Online here.

Simpson and Hagel [2006] : Simpson, R. Hope and D.K. Hagel. Mycenaean Fortifications, Highways, Dams and Canals. Paul Äströms Förlag. Sweden. 2006. ISBN: 978-917081-212-5.

Starkovich [2012] : Starkovich, Britt M., 'Fallow Deer (Dama dama) Hunting During the Late Pleistocene at Klissoura Cave 1 (Peloponnese, Greece)', Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte (21), 11-36. 2012. Online here.

Stiner et al. [2010] : Stiner, Mary C. Janusz K. Kozlowski, Steven L. Kuhn, Panagiotis Karkanas and Margarita Koumouzelis, 'Klissoura Cave 1 and the Upper Paleolithic of Southern Greece in Cultural and Ecological Contexts', Eurasian Prehistory, (7:1) 309–321. 2010. Online here.

Storemyr [2021] : Storemyr, Per. 'The ancient game traps at Gharb Aswan and across Lower Nubia (north-east Africa)', pp. 361-398 in A. Betts & W. P. van Pelt (Eds.), <i>The Gazelle’s Dream: Game Drives of the Old and New Worlds</i>, Sydney University Press. 2021. Online here.

Watson [1913] : Watson, William J., 'Aoibhinn an Obair an t-Sealg', The Celtic Review (9:34), 156-168. 1913. Online here.

Wiseman [1966] : Wiseman, James R., 'A Trans-Isthmian Fortification Wall', Hesperia (32:3) 248-275. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1963. Online here.

Zedeño et al. [2014] : Zedeño, Maria Nieves with Jesse A. M. Ballenger and John R. Murray. 'Landscape Engineering and Organizational Complexity among Late Prehistoric Bison Hunters of the Northwestern Plains', Current Anthropology, (55:1), pp. 23-58 . 2014. Online here