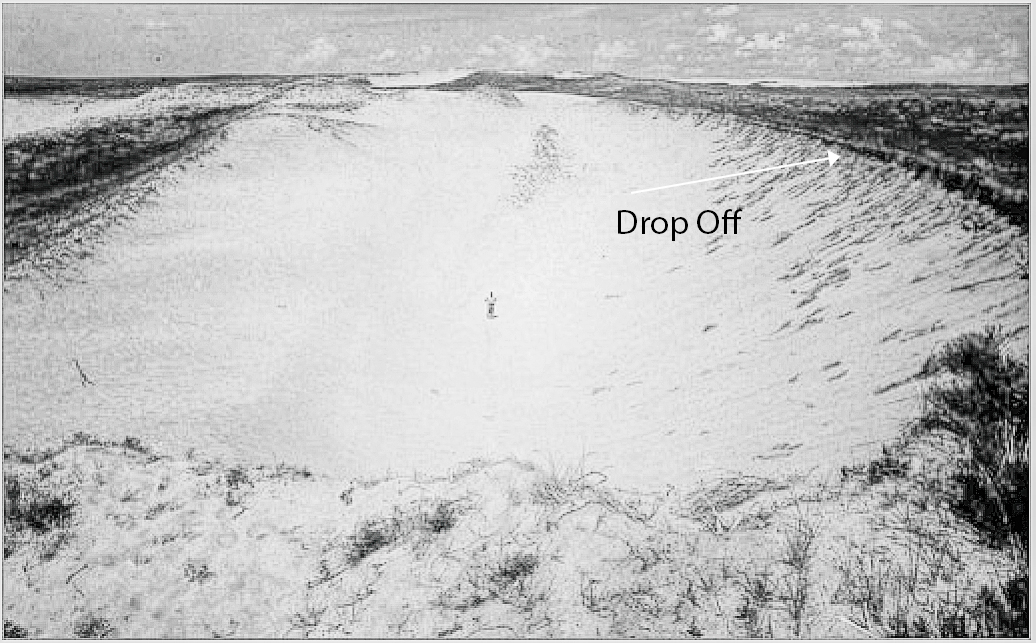

In Galway, Scotland, there is a long and narrow valley called 'The Glen of the Bar' (55.007825° N, 4.379391° W). It is about half a kilometer long and rapidly narrows from ~70 m to about 10 m at its head.

|

| Figure 1. Glen of the Bar, facing NE to the valley head. |

|

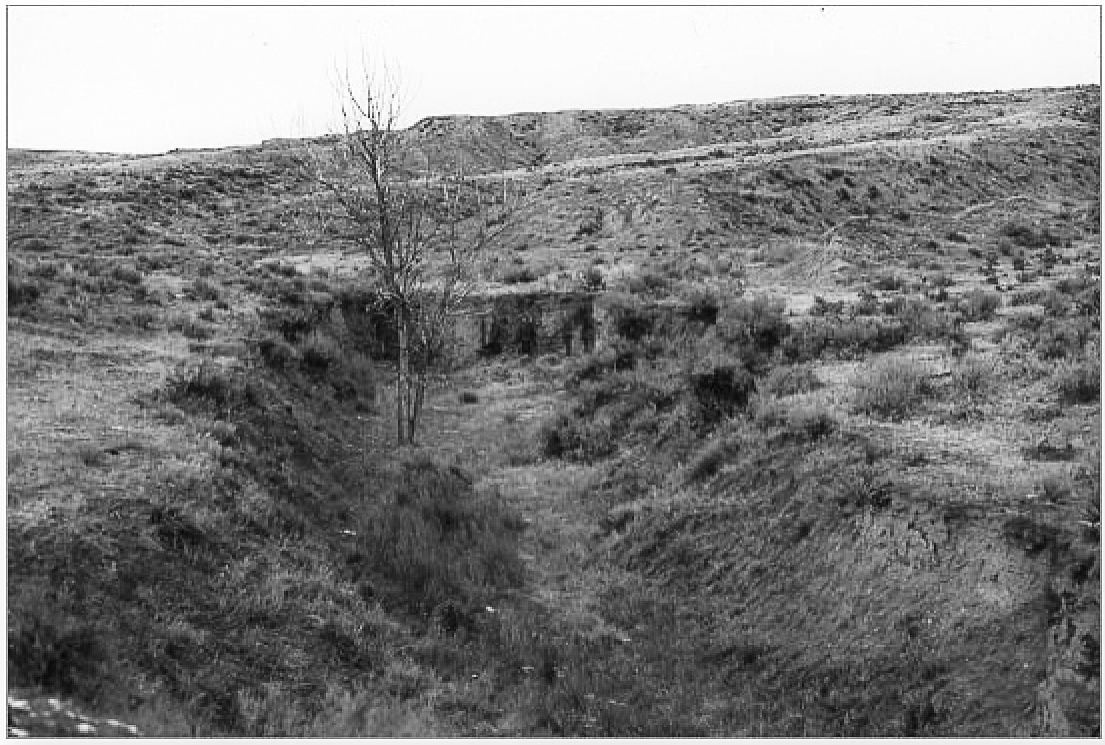

| Figure 2. Visitor's outlook. Glen of the Bar, looking SW from valley head. |

The Glen of the Bar was, in former days, reputed as a deer trap or 'elrick'.[1] In this case deer would be driven by beaters up the narrowing valley until, at the last moment, they come over a rise and into an impound - up to this point invisible[2]. The corral or impound would have been just where the visitors' outlook is shown in figure 2. An 'elrick' [3] is a deer trap consisting of a narrow defile (or even parallel walls) that narrows into an impound or corral in which game may be killed or captured (perhaps in nets). Communal hunting often makes use of narrow defiles or narrowing valleys to force game into such a tight spot that the animals can neither maneuver nor escape. Once animals are in that position they are easy prey for the hunter's arrow.

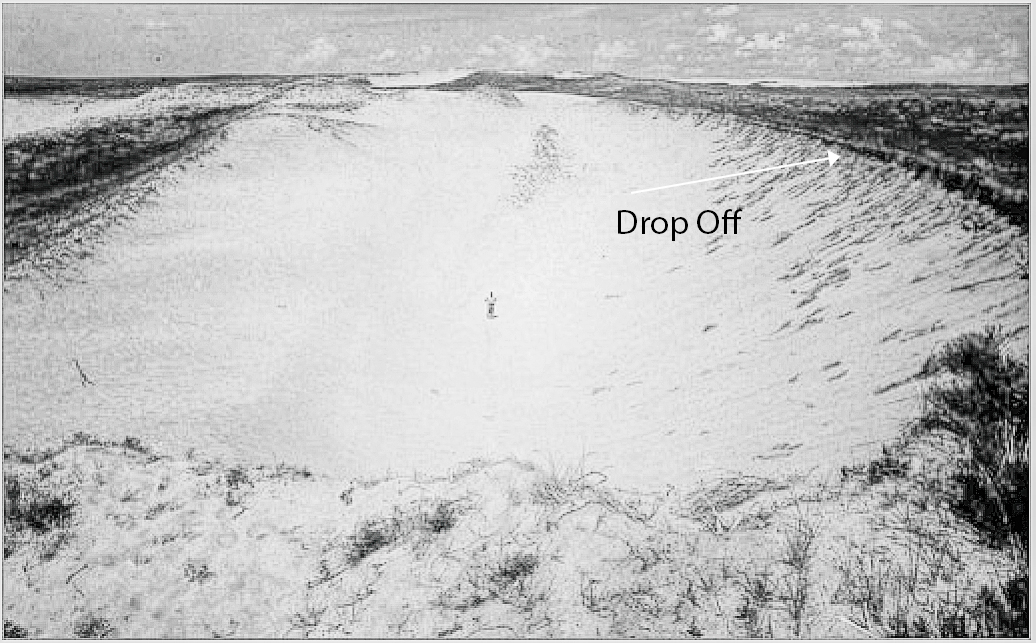

Besides the Glen of the Bar and other narrow defiles a classic case of game trap implementation is the use of lunate or parabolic sand dunes for trapping antelope. Once the animals are driven between the arms of the sand dune it is almost impossible for them to get out. The photograph shows why this is so. The sand dune shown here is some hundreds of meters long and, perhaps, 80 meters wide.

|

| Figure 3. A parabolic sand dune in the American South-West. [4] |

Antelope driven into this dune will try to climb out. And yet if my readers look closely they will notice that, right at the edge of the dune, plant roots have held the sand nearly vertical for a distance of about two or three feet. It is very difficult for any animal to overcome this vertical lip. Animals exhaust themselves in the attempt and are killed. Many ungulates are superb jumpers and climbers but topography can be employed in such a way to negate those advantages. In this sense they function just like the intermittent wall segments on the side of Mytika.

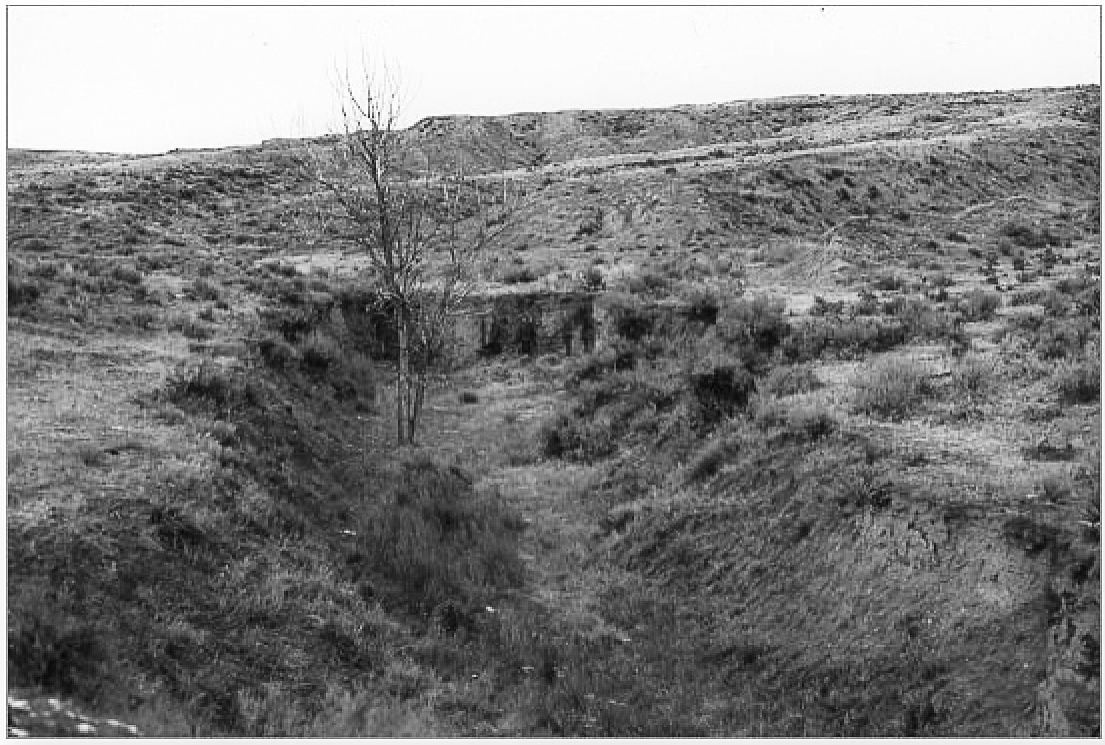

In the American west there often occur 'headcut' arroyos. These are defiles which are erosion cut by streams. In the process of their formation the upper end collapses into a vertical wall. The illustration shows what this looks like. Such arroyos are often the site of communal mass kills. [5]

|

| Figure 4. A headcut arroyo. |

La Roche de Solutré (46.299401° N, 4.719246° E) is a limestone outcropping in Burgundy, France. I show it in the next picture.

|

Figure 4a. The Rock of Solutre (Roche de Solutré) in Burgundy.

|

For about 20,000 years it was the site of communal hunts of wild horses. The actual site contains the remains of between 30,000 and 100,000 horses. It is the premier site for prehistoric communal hunting in western Europe and proves that this form of hunting was understood as early as the Upper Paleolithic.[5a] At one time it was believed that horses were herded up to the top of the rock and then forced to fall over killing them. This thesis was debunked by some simple reflections on the behavior of horses. Horses are not buffalo which travel in enormous herds. Horses travel in small bands of several females led by a stallion. The essence of the fall trap is a large number of animals which, by crowding, force those up front over the edge. This is a situation which cannot be provoked among horses.

Instead it appears that when horses regularly passed the rock on migrations that men could spook them and change their direction until they were trapped in a naturally occurring canyon. Here they could be killed by waiting hunters.[5b] The situation is hypothesized in the following picture.[5c]

What does this have to do with the valley between Mytika and Rachi?

We should start by facing facts. No evidence has ever been produced to show that the 'Cyclopean' wall was intended to cross the Isthmus. No evidence has ever been produced to indicate that the wall continued along the eastern side of the Rachi (about 970 m). No evidence has ever been produced to indicate that the wall on the Mytika side was continuous and all we can conclude is that these segments were constructed ad hoc and, potentially, for differing purposes.

A brook flows from the head of the valley and north-south through its entire length. In antiquity this would have been a natural habitat for grazing ungulates [6] as well as many other types of game. The flat valley bottom, gentle slope up to the head, the availability of water all allow us to suppose that this valley was a natural migratory route to and from the top of Mytika plateau where there would have been the abundant grassland for grazing.[7] The area was "little inhabited" during the Bronze Age. We know that the Mycenaeans were avid hunters of deer. Many depictions of deer and deer-hunting figure in LH rings, cups, fresco, and pottery.

The entire valley between Mytika plateau and the Rachi is not inconsistent with a communal game-drive system.[8] It bears a strong resemblance to the Glen of the Bar and many other such elricks. That the segments Pe and Ge flare away from each other is a good indication that they were intended to be the beginnings of the 'antennae' or 'rays' of such a system. The sequence Pe, Sp, Zo, Vl, and Pa steepen the W side of the Mytika plateau against which game would be driven.

|

| Figure 5. The game-drive system in the Rachi-Mytika valley. The 'Beaters' drive the game into the space between the 'rays' or 'antennae' at Mi-Ge and Pe. 'Stationary' refers to figures standing on the Rachci in outline against the sky. Because of those figures the game will move further up into the valley and to the E where they encounter either the 'Shooters' or the 'Impound' where they may be captured or killed. The 'Coast Road Ddefence' is a completely separate structure. |

If they were meant to contain deer then we should not expect to find any of these wall segments to be of a height of more than 3 m. which is more than high enough to defeat the jumping behavior of deer.[9] When in use there would be several positions along the Mytika valley wall from which shooters would kill game. This 'wall' need not be continuous along the whole line of the western Mytika slope. On the steep Rachi side there are no walls nor would we expect to find them. A line of 10 - 20 human figures standing against the skyline on the top of that ridge would be quite enough to drive game to the eastern side of the valley.

Alternatively one would employ cairns with 'scares'[10] to accomplish the same purpose. The fact that Mi only begins where the Rachi comes back to the level is highly indicative that the Mi-Ge sequence was the beginning of an 'antenna' or 'ray'. Nothing that we know about the complex of wall segments in Broneer's thesis contradicts this model.

My game-drive system hypothesis might, of course, be false. But it is far from absurd. And it is far more likely than an hypothesis that attempts to relate archaeological finds to semi-mythological and highly suppositious 'events'.[11]

We know for a fact that the Mycenaeans were avid hunters and we know that they hunted the sort of game for which game drive systems are most efficient. Possible quarry for them would have included the aurochs (Bos primigenius) as well as the red deer (Cervus elaphus) which has been hunted in Greece during prehistoric as well as historic times. Other very likely game would be fallow deer (Dama dama) and roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). Literature and art also shows us that they were aficionados of boar hunting (Sus scrofa). Nor must we forget the mainstay of the Mycenaean animal economy, ordinary cattle (Bos taurus).

Not very far from here the narrow valley at Klissoura[12] was used by Mesolithic people (long before greek-speakers came to Greece, of course) to trap and kill fallow deer which they seem to have done in large numbers. There are examples of this hunting style from about this same time in Epirus.[13]

Falsification

All good hypotheses should be falsifiable. How would we attack this game-drive hypothesis?

a. The fastest way would be to support Broneer's hypothesis by discovering evidence that this was a cross-Isthmus wall intended for defensive purposes. Additional fragments of the wall that indicated some clear direction might suffice. It would also suffice to show defensive features: real towers, for example. Such things would not be consistent with a game-drive system. And, in order to be a protective wall, it need not have been completed. There are other examples of partly completed walls on the Isthmus and those were certainly of a defensive nature. [14]

In fact I would not discount the probability of finding continuations of Mi-Ge. But, if so, I think those segments would be found around the Sacred Glen - a prime candidate for a game-drive system in its own right. Game-drive systems are often chained and that could be the case here. See figure 6.

|

| Figure 6. Hypothetical game-drive system at the Sacred Glen. |

b. As far as I am aware no one has proposed a convincing model of communal hunting anywhere else in Greece (or, at least, not in the BA). 'Absence of evidence' certainly would point in that direction. A continuing dearth of such findings might significantly undercut my hypothesis. But hunting in these societies leaves few material traces and is, perhaps, simply understudied or even, not studied at all. One thing archaeologists could do is very simple - search for arrowheads at the foot of Sp, for example. [15] Another approach might be to re-examine the Mycenaean landscape for locations that would suggest hunting in the LBA. The Klissoura valley wouldn't be the worst place to start.

c. The remains of Mycenaean feasting might show inordinately low amounts of wild game in the Mycenaean diet. This would definitely undermine my thesis. But I suspect what researchers would find is that in the fully-developed Mycenaean system of LH III hunting was effectively restricted to the upper-most classes. This sociological divide has been known in other places.

I regard the likelihood of any of criteria a through c as very unlikely to be realized but - maybe.

In the meantime I emphasize that my proposed model would explain, not only the 'missing wall' on the Rachi side, but also the curious 'southern salient' in Broneer's proposed wall route. In the game-drive model this 'southern salient' is no longer an anomaly. It is the whole point.

Dr. Broneer tried to base his hypothesis on the mythology of the 'Return of the Herakleidai'.[16] Thinking about what the Mycenaean people ate would be a more productive approach.

Footnotes

[1] Fletcher [2011] pos. 8397. An 'elrick' is a deer trap. Fletcher, pos. 1583 says "We begin to build up the picture of a gradation of deer enclosures from prehistory to the present, extending from the simple elrick or narrow defile into which deer might be driven for slaughter or capture, or through permanent or even temporary wings for capture in nets, to the enclosures into which deer might be enticed using browse such as ivy as previously discussed, to the fully enclosed ... deer park."

[2] Animal game drive corridors are almost always directed in such a way tthat the ultimate shooting positions, or the impound, etc. are invisible until the very last moment. E.g. Kornfeld et al. [2016] 388: "Before the lane reaches the entrance to the corral, there is a deliberate bend, obscuring the corral entrance until the last possible moment ... ". Mandelbaum [1940] 254, Fig. 5 illustrates a Cree buffalo impound which exhibits a similar sharp, last minute, bend, just before the impound itself. Brochier et al. [2014] 28 emphasize that, of the upslope game drive traps he and his team studied in Armenia, 81% had such a slope break.

[3] Wiseman [2007] 244-5. " ... elerc seems to stem from Old Irish erelc, 'an ambush', which through metathesis later became in Gaelic either eileirig or iolairig, 'a deer-trap', i.e. a funnel shaped defile or V-shaped trap, either natural or artificial, into which deer were driven in order to be culled."

[4] Kornfeld et al. [2016] 345-6.

[5] Ibid. 318. " Since headcuts in dry arroyos often formed barriers that prevented further movement upstream by bison, and the slopes of the adjacent walls of the arroyos were usually high enough and steep enough to contain the animals, these landforms were ideal for trapping the animals (Figure 4.6)." There are many examples in Kornfeld et al. For example (p. 368) the Hawken site in Wyoming: "The Hawken site is a classic example of the arroyo bison trap; at least 80 animals were driven up the bottom of the arroyo by hunters until a perpendicular headcut was reached ... ". And see the headcut trap in Agate Basin, Wyoming, pp. 318, 329, 338; the Carter-McGee site in the Powder River Basin in northern Wyoming, 330, 361; the Frasca and Nelson sites in NE Colorado, 362; and the Powder River again on p. 377, ""The banks of the arroyo at the time of the kill were believed to have been nearly vertical and 5–10 m high. The headcut that makes the trap was formed in more resistant strata in the Fort Union Formation ... "

[5a] Olsen [1989] 295, "By the Upper Palaeolithic, there is considerable evidence that humans were very efficient communal hunters of large game."

[5b] Ibid., 316, 323.

[5c] Ibid., map: Fig. 2 from 297.

[6] Roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), Red deer(Cervus elaphus), Fallow deer (Dama dama), Aurochs (Bos primigenius), wild boar (Sus scrofa).

[7] 'natural migratory route'. With the destruction of the deer in Greece we'll never know for sure. Red deer survive in Greece only as a small herd on Parnitha. The fallow deer survives in small herds on Rhodes. There is no Capreolus in Greece to my knowledge. The last aurochs died in Poland in 1627. Wild boar survives in Greece but not, to my knowledge, in this area.

[9] They don't need to be higher for game. Deer are at a disadvantage jumping from below a wall. Red deer can clear 8 - 12 ft. (2.43 - 3.65 m) on the level but will only jump the greater heights when frightened or otherwise motivated (mating, food, alarm). This is true particularly if they have a running start. Jumping much higher than that seems to put them at risk of injury. Commercial estimates for required fence heights to constrain deer come in at somewhat less than that. This is probably because the use of most commercial fences is merely to discourage deer and not keep them out under all circumstances (which can be significantly more expensive). In a true game-drive system beaters would often be visible on the walls and the animals will instinctively shy back to the middle.

Fence height figures from howtorewild.co.uk:

Capreolus capreolus (roe deer): 150 cm. (4.92 ft.)

Cervus elaphus (red deer): 180 cm (5.9 ft.)

Dama dama (Fallow deer): 150 cm. (4.92 ft.)

[10] 'Scares'. A common technique in the Arctic, for example. Walls in the Arctic game-drive systems often are decorated with sticks to which fluttering flags are attached. See Benedict [2005] 427. The word in Latin is 'formido' which is defined as a rope strung with feathers used by hunters to scare game. Hunters using nets with scares (formido) attached is described in Peck [1898] s.v. 'Rete' as '"This range of nets was flanked by cords, to which feathers dyed scarlet and of other bright colors were tied, so as to flare and flutter in the wind." Fletcher [2011] pos. 2063 describes the Ring Hunt: " ... once within a circle about the diameter of a league, about three miles, the animals were enclosed by a rope on which pieces of felt were hung. The hunters could then enter the circle and begin to kill them usually from horseback with bow and arrows." Emphasis is mine.

[11] Broneer [1966] 357. "These deductions are in agreement ... " Whatever else we may say about Broneer's arguments (and, in fact, most arguments in this field) is that they are not deductions.

[12] For Klissoura: Stiner et al [2010]; Starkovich [2012].

[13] Epirus. Sturdy et al. [1997] present a careful analysis of animal routes and habitats in Paleolithic Epirus. They present (601) a model of animal capture and control in the area of the Asprochaliko gorge which greatly resembles this one.

[14] Discussed in Wiseman [1963], Wiseman [1978] 59-63. The best and most recent survey may be in Gregory [1993] 4-6. Gregory discusses not just the several walls but the strategic considerations which govern the defense of the Peloponnese from threats on the north.

[15] Arrowheads have been found at the ends of one or two 'Cursus' in Britain. At Woldgate Cursus in Humberside, for example:

|

Figure 7. Arrow heads found at one end of Woldgate Cursus.

Clearly this indicates the shooting position. |

To my way of thinking this supports the overwhelmingly likely idea that the cursus was intended to drive game. And see Fletcher [2011] pos. 1077 on the cursus: "I hesitate to suggest that they may ever have served as a means for killing deer ... but similar constructions were later to be used to direct deer."

[16] An example of the syndrome which I have named 'making Homer true'. Archaeological finds can, perhaps, be used in responsible support of materials derived from epic literature or mythology (or vice versa). A fine example of such responsible handling is in Robert Buck's History of Boeotia.when he comes to examine the founding myths of Thebes vs. what can be learned from archaeology and other sources.

Bibliography

Anderson [1985] : Anderson, J.K., Hunting in the Ancient World, University of California Press, Berkeley, California. 1985. ISBN 0-520-05197-1.

Barringer [2001] : Barringer, Judith. The Hunt in Ancient Greece, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London. 2001. ISBN 0-8018-6656-1

Brochier et al. [2014] : Brochier, Jacques Élie with Olivier Barge, Christine Chataigner, Marie-Laure Chambrade, Arkadi Karakhanyan, Iren Kalantaryan, Frédéric Magnin. 'Kites on the margins. The Aragats kites in Armenia', Paléorient (40:1), pp. 25-53. 2014.

Buck, Robert [1979] : Robert Buck, A History of Boeotia. University of Alberta Press, ISBN: 978-0888640512

Fletcher [2011] : Fletcher; John. Gardens of Earthly Delight: The History of Deer Parks. Windgather Press. Kindle Edition. 2011.

Gregory [1993] : Gregory, Timothy E., Isthmia V. The Hexamilion and the Fortress, American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Princeton, New Jersey. 1993. ISBN: 0-87661-935-9.

Kornfeld et al. [2016]3 : Kornfeld, Marcel with George C. Frison, and Mary Lou Larson. Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies, Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group. London and New York. 2016. ISBN 978-0-12-268561-3.

McOmish and Tuck [2002] : 'The Woldgate Cursus; Humberside, Survey Report', Archaeological Investigation Series. 2002. Online here.

Olsen

[1989] : Olsen, Sandra. 'Solutré: A theoretical approach to the

reconstruction of Upper Palaeolithic hunting strategies',

Journal of Human Evolution (18:4) pp. 295–327. 1989.

Starkovich [2012] : Starkovich, Britt M., 'Fallow Deer (Dama dama) Hunting During the Late Pleistocene at Klissoura Cave 1 (Peloponnese, Greece)', Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte (21), 11-36. 2012. Online here.

Stiner et al. [2010] : Stiner, Mary C. with Janusz K. Kozłowski, Steven L. Kuhn, Panagiotis Karkanas, and Margarita Koumouzelis, 'Klissoura Cave 1 and the Upper Paleolithic of Southern Greece in Cultural and Ecological Context', Eurasian Prehistory, (7:1) 309–321. 2010. Online here.

Sturdy et al. [1997] : Sturdy, Derek with Derrick Webley and Geoff Bailey. 'The palaeolithic geography of Epirus'. pgs. 587–614 in G. Bailey (ed.) Klithi: Palaeolithic Settlement and Quaternary Landscapes in Northwest Greece: Volume 2: Klithi in its local and regional setting. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. 1997. Online here.

Wiseman [2007] : Wiseman, Andrew E.M., Chasing the Deer: Hunting Iconography, Literature and Tradition of the Scottish Highlands, University of Ediburgh. 2007. Online here.

Wiseman [1963] : Wiseman, James R., 'A Trans-Isthmian Fortification Wall', Hesperia; The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens [32:3], pp. 248-275, The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1963. Online here.

Wiseman [1978] : Wiseman, James. The Land of the Ancient Corinthians. Paul Åströms Förlag, Göteborg, Sweden. 1978. ISBN: 91-85058-78-5.